In November 1952, Israel’s first President, Chaim Weizman, passed away. In his search for a worthy candidate, David Ben-Gurion approached a Jew with a world-famous reputation and international standing – Albert Einstein.

Although he was moved by Ben-Gurion’s request to become President of Israel, Einstein turned it down and wrote to Ben-Gurion saying:

I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it. All my life I have dealt with objective matters, hence I lack both the natural aptitude and the experience to deal properly with people and to exercise official functions.

Ben-Gurion related that he had also thought to appoint a President of Yemenite descent, but if there was no choice but to have an Ashkenazi President, this should be someone who was popular with Israelis from all walks of life. Ben-Gurion thought that the most suitable person in this case would be Izhak Ben-Zvi, and he approached him with this request. Ben-Zvi agreed, but only on three conditions. These conditions are a fair reflection of his character, his personal biography and the values which guided him until his Presidency and beyond.

Izhak Ben-Zvi’s first condition was that the President’s official residence should be in Jerusalem. During Chaim Weizman’s term, the official residence was in Rechovot, and it comes as no surprise that Ben-Zvi requested that it move to Jerusalem. His biography shows that that from his arrival in the Land of Israel, Izhak Ben-Zvi tied his fate to Jerusalem. Unlike most of his friends, pioneers of the Second Aliya who settled in the north of the country, the area of the Sea of Galiliee and the Jezreel Valley, and joined collective settlements all over the country, Ben-Zvi and his future wife, Rachel Yanait, settled in Jerusalem, a city which symbolized the opposite of everything the pioneers of the Second Aliya stood for.

Ben-Zvi arrived in Jerusalem a year after arriving in Palestine, and joined the “Jerusalem Commune”, a small but vibrant group of pioneers, made up of both native-born Jews and new immigrants, who wanted to establish a “New Jerusalem”. They tried to introduce Zionist ideals to the conservative local inhabitants who lived a traditional life and to convey the importance of leading a productive life. They did this in a variety of ways which included teaching Hebrew to immigrants from Persia in the Nachlaot neighborhood, founding the Hebrew Gymnasium in Rechavia (Jerusalem's first, and the country’s second modern Jewish high school) and the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, establishing the He-achdut newspaper and leading the first workers’ strike in the city.

About Jerusalem Izhak Ben-Zvi wrote:

This city is indeed one of a kind, not only in the world, but also in the Land of Israel. And more than the country’s influence can be felt in the city, it is the influence of the city which can be felt in the land… the chain which connects the glorious past with the dark future, the forefathers’ heroism with the sons’ hope – nowhere is this felt more than in the city of Jerusalem.

Several year later the commune dispersed and the members went their own way. Rachel Yanait left to study agronomy in France, and Izhak and his friend, David Ben-Gurion, went to study law in Constantinople. Their studies were cut short by WWI, and their attempts to find places in the Ottoman administration failed. Their Zionist activities led to their deportation from Palestine. They travelled to the United States and organized recruitment to the Jewish Legion in the British army, in which they both served.

After the war, Izhak Ben-Zvi and David Ben-Gurion came back to Palestine, and Ben-Zvi settled in Jerusalem. Following his marriage to his Rachel Yanait, the couple built a modest cabin in Rehavia, where they raised their two sons, Amram and Eli. Their extended family also lived in the cabin, and it was the site of frequent meetings of the Yishuv and Haganah leadership.

When Ben-Gurion approached Ben-Zvi to be Israel’s second President, it was clear that he would not leave the city where he had lived for decades, and that the city’s special status dictated that it should be the site of the Presidential residence.

But where in Jerusalem should the Presidential residence be?

After the government had agreed to locate the President’s official residence in Jerusalem, a suitable site in the city still had to be found. To the proposal to buy the Schoken villa which was empty at the time, Izhak and Rachel wrote the following, explaining why they had no intention of moving to the villa:

We are simple people. We have always lived with the common people, sharing their joys and sorrows. We are not fond of luxury and would like to live the same lifestyle to which we have become accustomed. The little cabin was the Haganah center in Jerusalem, it was where we met with the people of the Third Aliya, and where our sons Amram and Eli grew up. We have found out that the government would like us to live in the Schocken mansion, but we will not leave this little corner of ours, where our cabin stood. We strongly desire to continue living a simple life.

Their refusal to move to a luxurious residence was Rachel and Izhak’s second condition. Such a move would have been in complete contradiction to their modest lifestyle. The couple stated that at a time when most Israelis were living in transit camps, huts, shacks and other makeshift dwellings, it was inconceivable that they would live in a mansion.

So where should the Residence be?

Should the President’s Residence be his own private house, as during Chaim Weizman’s term? At the time, Rachel and Izhak lived in a small, three-roomed apartment in an apartment block which had been built on the site of their cabin. The cabin itself had been moved in the 1950’s to Kibbutz Beit Keshet in the north, where their son Eli, one of the kibbutz’ founders, had been killed during the War of Independence.

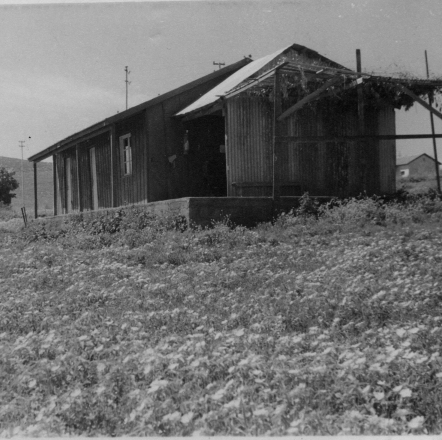

This small apartment was clearly unsuitable to be used as the President’s chambers or as an official reception hall. Therefore Izhak Ben-Zvi made a suggestion – another cabin. And thus, on the grounds next to their apartment, where until the end of the 1920’s Rachel’s Women’s Workers Farm had been, two cabins were built to serve as the President of Israel’s official reception halls. Various artistic objects and archeological finds were placed on exhibit in the halls, reflecting the landscapes of Israel and symbolizing the Jewish people’s return to their land, and the atmosphere was one of simplicity and modesty.

The President’s modesty in refusing to move to a luxurious mansion became well-known. For many years, Izhak Ben-Zvi fought the Knesset’s attempts to raise his salary, and towards the end of his term, it turned out that the President’s driver was making almost twice as much as the President himself. When Ben-Zvi was out of the country on an official visit to Africa, the Knesset’s Financial Committee took advantage of his absence and raised his salary. In response, Izhak Ben-Zvi wrote the following to the Committee’s chairman:

To Yisrael Guri, Jerusalem

Jerusalem, 31.12.1962

Since taking office, I have viewed with great alarm the dizzying race after the standard of living in our state as one of the serious risks to the financial independence we so long for. In my opinion, as long as we are obliged to fulfill these two important missions – bringing our brothers to the country and absorbing them here, and improving our security in face of the perils lurking outside our borders, we cannot be dragged into a race to improve our standard of living. This is the reason I objected in principle to raising my salary, in the hope of serving as an example to others, and I repeated my objection year after year, both when reviewing my office’s budget and in personal conversations with you.

In previous years, the Financial Committee took my views into consideration and agreed to leave my salary without raising it at all for eight years. But this year, and in spite of my objections, the Committee decided, when I was out of the country… to raise my salary to 18,000 Israeli pounds a year.

In a recent conversation we had, you told me the Knesset and the Committee’s reason for acting as they did. I did not see any way to I could refuse, but I have decided to use at the very most half of my salary for my personal needs and to dedicate the other half to a special fund for the preparation for study and publication of original historical manuscripts about the history of the people and the Land of Israel.

The President’s Residence was located in Rehavia for twenty years: the eleven years of Ben-Zvi’s term and nine out of the ten years of the term of third President, Zalman Shazar. After this time, the Residence was moved to the newly-constructed house in Talbiyya, which is still in use at the present. In 2010 the Cabin was declared a National Heritage Site, and it was restored and renovated. Today visitors can tour the Cabin and see its unique original design just as it was in Ben-Zvi’s days.

And what about the third condition?

Izhak Ben-Zvi’s third condition was that he would accept the post of President only if he were allowed to continue the research he had been engaged in all his adult life – the study of the Land of Israel and its settlement, and of Jewish communities in the East.

Izhak Ben-Zvi – then Shimshelevich – first came to Palestine in 1904 on a visit, and took part in an archeological dig in Tel Gezer. At night, as the moon rose, he wrote down his impressions:

Solemn thoughts arise and whirl through me; I am beside myself. Here is an era, dead in the ground, and people come and dig it up, relic by relic, shard by shard, and connect relic to relic, shard to shard and the bygone era rises up before our very eyes. Will we not be able to connect the relics of our nation – bone to bone – until it rises up and comes to life?” (from an article in the Hadoar paper, Krakow, 14.10.1904)

It seems that from that very moment, Ben-Zvi realized that he wanted to fill the role of archaeologist of the Jewish People, who would work to locate lost and dispersed shards from all over the world and join them in one magnificent vessel. The resemblance to the Vision of the Dry Bones is obvious, and it comes as no surprise that years later, Ben-Zvi chose to place a highly relevant verse upon the walls of the Cabin in Rehavia: ““Behold, I will take the people of Israel from the nations among which they have gone, and will gather them from all around, and bring them to their own land.” (Ezekiel 37: 21)

At that pivotal moment in Tel Gezer, when he was only 20 years old, Izhak Ben-Zvi resolved to dedicate his life to the study and documentation of Jewish communities, near and far. He soon realized that he would have to learn Arabic and so immediately upon his arrival in the country in 1906, he began learning the language systematically. He learned to speak it perfectly and formed close ties with both Jews and non-Jews alike.

Ben-Zvi travelled through the land and throughout the Middle East in search of Jewish communities, and documented his travel in his journals. He collected precious information about the people he met, their traditions and customs, as well as information about Jewish sites which had vanished over the years. He dedicated much of his time to the study of Sephardic Jewish communities and Jewish communities in the Middle East. Deeply concerned for the fate of these communities’ unique and rich heritage, on December 2nd 1947, following the UN decision on the partition of Palestine, Ben-Zvi established the Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East, which is still active today.

As President, Ben-Zvi initiated meetings marking the new month (Rosh chodesh) which were held in the President'sl Cabin. These events were dedicated to various Jewish communities, especially those from Muslim countries. At the first of these gatherings, Ben-Zvi said:

Today we are embarking upon a series of meetings for Rosh chodesh ,dedicated to the Tribes of Israel, immigrants from all the diasporas, first and foremost those from the Ishmaelite diasporas. Our aspiration is to nurture, as much as we are able, the process of bringing together the tribes of Israel returning to their homeland […]. We intend to raise the sparks of radiance hidden in all the tribes of Israel, and to make them the legacy of the entire nation.

The President’s Cabin was to become a “sukka for the Tribes of Israel”. People from all walks of life in Israeli society, Jews and non-Jews, sent the President and his wife many gifts, large and small, to share their moments of joy and happiness with them. All these gifts, simple and exepensive, from kindergarten children and well-known artists, were kept in the cabin.

Ben-Zvi dedicated his time to the study of the Land of Israel and its settlement as well. He and his wife travelled all over the country and met many people; these meetings too were recorded by Ben-Zvi in his notebooks. The unique testimonies he left in his notebooks are of immense value, since the following years changed beyond recognition the reality which he documented.

Izhak Ben-Zvi published 15 books and hundreds of articles about the history of the Land of Israel and Jewish communities.

After Ben-Zvi’s death, the Institute he founded was named after him – the Ben-Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East. Later on, Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi was established with the aim of commemorating Ben-Zvi’s memory by continuing the study of the topics to which he dedicated his life, and disseminating the knowledge gained from this study among the general public.

Izhak Ben-Zvi passed away on April 23rd, 1963, a few days before Israel’s 15th Independence Day. Following his request, he was not buried in the official plot reserved for Israel’s leaders on Mount Herzl, but rather in a commoner’s cemetery on Har Hamenuchot. His funeral procession was one of the most crowded in the country, and police and military forces were forced to intervene to maintain public order. Dozens of heartfelt eulogies were read out and telegrams of condolences were sent from countries all over the world, such as Hong Kong and Cuba which declared days of mourning for the beloved president.

David Ben-Gurion, Ben-Zvi’s old friend, eulogized him with the following words:

I had the privilege of working with Izhak Ben-Zvi since he arrived in the country in 1907, and I never knew a man so great in achievement and spirit and at the same time so humble, modest, and simple in all his ways with world leaders and with commoners like himself. He personified the love of the Jewish people and their unity in a way that no one has done before. The entire nation felt this. He won the love of the entire Jewish people as was vouchsafed to no other man in our generation or in those to come, a privilege to which there is no parallel among our people, divided as it is by a multitude of parties, communities and tribes.

The eulogy by Maariv’s mythological editor, Azriel Carlebach, was most apt:

Ben-Zvi’s era has come to an end. An era which left its mark on the status of Israel’s First Citizen. This is an era which elevated simplicity to a degree of nobility, modesty to the degree of opulence, power to the degree of humanity, and made the President’s house into a house for the nation in the full sense of the word

Izhak Ben-Zvi held the office of President longer than any other, and laid the foundations for this office as we know it today. The conditions under which he took this role upon himself shed a new and unique light on his personality and his achievements, before, during and after his Presidency.